HSUK’s ambition for high frequency, high quality and high speed services offering direct links between the UK’s principal cities exactly matches the aim of the HS2 project for ‘hugely enhanced capacity and connectivity between our major conurbations’.

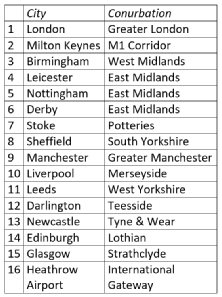

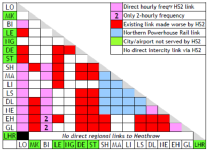

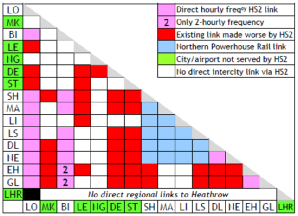

To measure HSUK’s and HS2’s performance, we’ve chosen 15 cities to represent the major conurbations (of Greater London, the Midlands, the North and Scotland) that fall within the scope of the HS2 project. We’ve also included Heathrow Airport to represent the needs of all regional cities for international/intercontinental links.

That’s 16 destinations, and 120 possible journeys between them… 119 if you discount London to Heathrow as being outside the scope of any interurban high speed line.

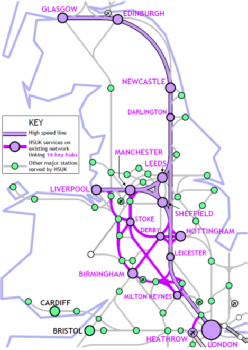

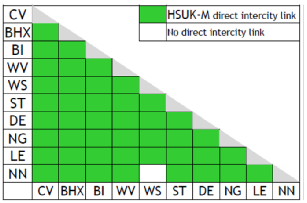

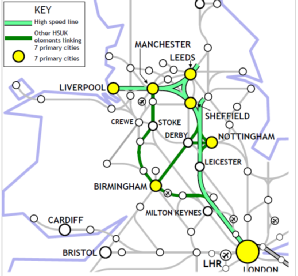

HSUK’s ‘spine and spur’ network of dedicated new high speed lines is closely aligned with 13 of these destinations. With HSUK’s new lines designed either to pass through city centre stations, or with the necessary connections provided to the existing network, HSUK will on its own fully interconnect most of the UK’s major conurbations.

Only Birmingham, Stoke and Heathrow are located at a significant distance from HSUK’s new lines, and for these centres a programme of major upgrades to existing routes, combined with limited new-

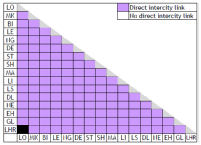

With all these interventions in place, HSUK can offer improved direct connections for 119 out of 119 possible journeys. This is unarguably the ‘hugely enhanced… connectivity’ for which the HS2 project was remitted.

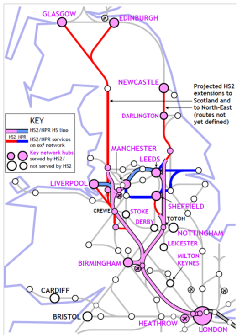

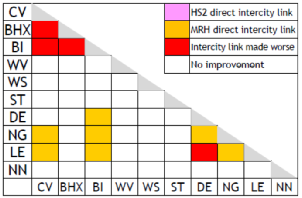

By contrast, HS2 fails badly against this basic requirement, offering only 18 improved direct connections out of a possible 119.

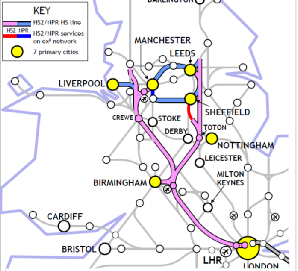

Its new high speed lines are fundamentally London-

Moreover, with no effective integration with the existing network, most communities will be bypassed by HS2, and left with reduced intercity services on the existing main lines; indeed, 6 of the 16 centres considered in this analysis will not be served by HS2.

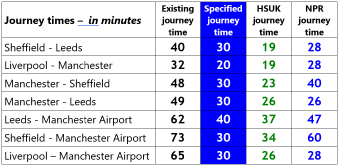

The belated Northern Powerhouse initiative for ‘HS3’ transpennine high speed lines linking Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds will do little to address the HS2 project’s connectivity failure.

Even if implemented in full accordance with its specification (see Objective 4) it will only improve an additional 14 journeys, giving the Government’s HS2 project a meagre overall score of 32 improved direct connections out of 119, and a legacy of hard-

TABLE 1.1: Major Cities and Major Conurbations

Fig 1.3: HS2/NPR Core Network & Connectivity Performance

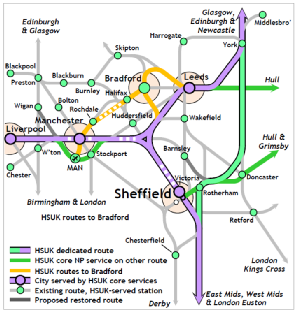

Fig 1.2: HSUK Core Network & Connectivity Performance

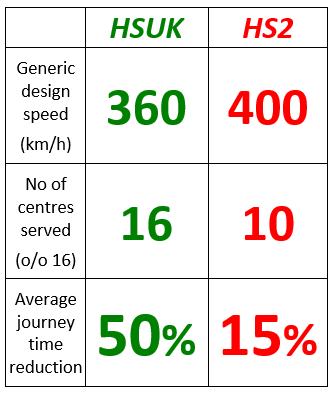

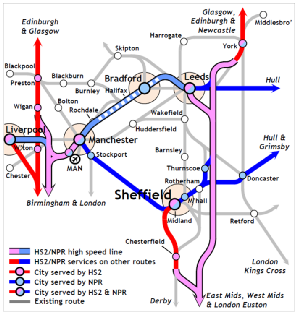

If you’re going to invest upwards of £100 billion in new high speed lines, it would be reasonable to expect dramatically reduced intercity journey times, and HSUK achieves exactly this.

The timetable developed for HSUK, based upon the route design of over 2,000km of new, upgraded and restored railway, shows that HSUK could achieve over 50% average journey time reductions between its 16 key network hubs.

By contrast, HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail will achieve at best around 15% average journey time reductions. HS2 and NPR will certainly achieve spectacular journey time reductions along their chosen lines of route, for instance between London, Manchester and Leeds.

But HS2’s lack of integration means that these journey time benefits cannot spread to the rest of the network where – due to the proposed service reductions – journey times may actually increase.

This failure to integrate has been driven by a quixotic decision to ‘future-

This would make HS2 the fastest railway in the world, but it has had the effect of driving HS2’s route away from established transport corridors onto intrusive rural alignments. This will have two highly adverse outcomes – it will hugely increase HS2’s environmental impact (see Objective 7), and it will preclude any possibility of effective integration with the existing rail network (see Objective 3).

This gives rise to a highly embarrassing paradox, whereby HSUK – designed for the lower maximum speed of 360km/h – can offer average journey time reductions (@ 50%) that are over 3 times greater than those of HS2 and NPR (@ 15%).

Table 2.1 : HSUK vs HS2 – Comparative Journey Time Savings

There are many criteria by which the performance of a national intercity network might be assessed. Aside from direct intercity connectivity (Objective 1) and optimised journey time reductions (Objective 2) there are many other considerations such as:

Capacity;

Integration;

Use of city centre stations;

Extent of network;

Development of timetable;

Design as a network.

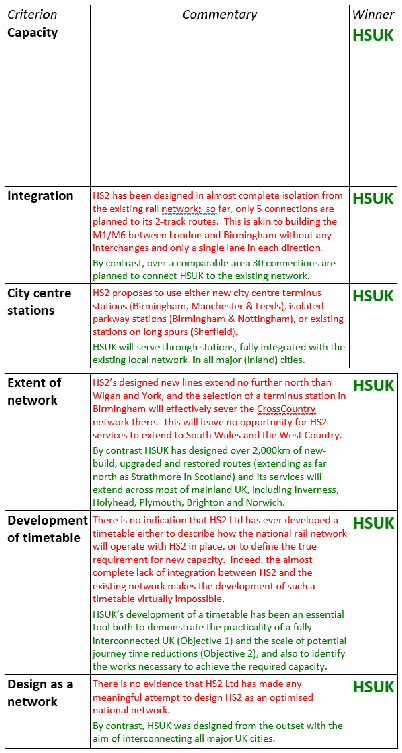

On all of these criteria, HSUK hugely outperforms HS2.

Table 3.1 : HSUK vs HS2 – Comparative Network Performance

Objective 4: A new transpennine main line for passengers and freight to link the key cities of the Northern Powerhouse

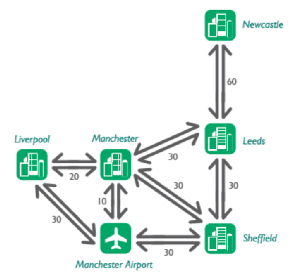

In 2014, the Government’s Northern Powerhouse initiative called for new ‘HS3’ high speed lines to connect the principal cities of the North.

This was a belated attempt to redress the failure of the HS2 ‘Y-

Subsequently Transport for the North (TfN) has developed the ‘HS3 Specification’ to include a) journey times to Hull and b) enhanced service frequencies, with 6 trains per hour (tph) required on routes interlinking Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds, and 2tph on routes to Manchester Airport.

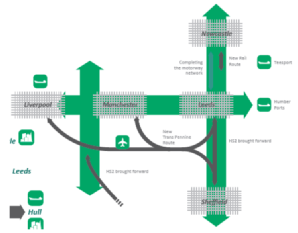

HSUK’s proposals in the North of England have required virtually no modification to satisfy the requirements of the HS3 Specification. Its transpennine main line, routed via the abandoned Woodhead corridor to Manchester and Liverpool, will connect with its ‘Yorkshire Loop’ linking Sheffield and Leeds, and this system will provide the required reduced journey times, at the required frequency, between all of the North’s major cities.

Comprehensive direct links to Manchester Airport will be established by transforming the present terminating branch to the airport into a ‘South Manchester Loop’, linking to the HSUK main line to the east and to the west of Manchester.

The Northern Powerhouse Rail proposals developed by Transport for the North fall far short of HSUK’s performance. Although a new transpennine main line is proposed to link Leeds and Manchester via Bradford, no equivalent new routes are proposed to link Sheffield (S) and Manchester (M) or Sheffield (S) and Leeds (L), and the limited upgrades that are proposed will fail to deliver either the journey times (S to M) or service frequencies (S to M and S to L) required by the HS3 Specification.

Under the TfN strategy, Sheffield – one of the UK’s 12 primary cities – will be effectively bypassed by both north-

This failure has happened because HS2’s north-

Instead, 2 new transpennine routes (i.e. Manchester to Leeds and Manchester to Sheffield) must be built to meet the HS3 Specification for journey time and service frequency.

As the alternative HSUK proposals demonstrate, the specified integration between HS2 and HS3 can only be achieved with the north-

Regrettably, TfN appears never to have challenged the established HS2 routes, or to have comprehended the fundamental contradiction of basing their Northern Powerhouse Rail proposals – whose core rationale is to transform transpennine connectivity – upon HS2’s northern routes – which were designed with no thought for transpennine connectivity.

Fig 4.1 : HS3 Journey Time Specification

Fig 4.2 : HS3 Routeing Specification

Fig 4.3:Key HSUK routes serving Northern Powerhouse

Table 4.4:HSUK & NPR journey times on key Northern Powerhouse routes

One of the principal selling points of the HS2 project has always been its ‘local capacity dividend’ – in other words, the benefits that the introduction of HS2’s new lines should bring to the local rail networks in the regional conurbations served by the HS2 project.

With the recent publication of Midlands Connect’s proposals for the ‘Midlands Rail Hub’, it’s at last possible to determine HS2’s success or failure in enabling improvements to the local rail network, and thereby achieving its aim of kickstarting the Midlands Engine.

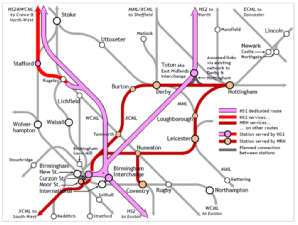

The Midlands Rail Hub (MRH) scheme fails because it is of necessity primarily directed at addressing HS2’s connectivity deficiencies within the Midlands, and its complete lack of integration with the existing network.

HS2 will offer no direct intercity links between West and East Midlands cities – so this task must fall upon the MRH scheme with its proposed upgrades along existing routes via Derby and Leicester.

HS2’s proposed Birmingham Curzon Street terminus is irretrievably disconnected from the main West Midlands rail hub at Birmingham New Street – so the MRH scheme is based upon restoring disused terminus platforms at Moor Street station, adjacent to Curzon Street. This will do nothing to improve connectivity to communities along the Wolverhampton/ Walsall/Coventry corridors, and it will leave Birmingham with 3 separate main line stations.

As a result, the MRH scheme will do little to improve the rail networks of the West and East Midlands. Out of 45 possible links between 10 principal centres (Coventry, Birmingham Airport, Birmingham, Walsall, Wolverhampton, Stoke, Derby, Nottingham, Leicester and Northampton), the MRH scheme will only improve 7 journeys.

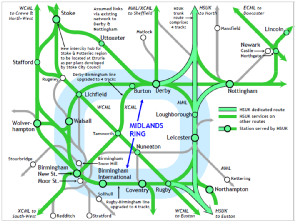

By contrast, HSUK’s strategy of concentrating high speed line construction along the M1 corridor, and of upgrading (to 4 tracks) or restoring key radial routes into Birmingham, will allow Birmingham New Street to maintain its status as the primary hub of both the local West Midlands network and also of the national intercity network.

HSUK’s integrated combination of new, upgraded and restored routes can then provide the new links and the extra capacity necessary for the establishment of a ‘Midlands Ring’ offering almost complete interconnect-

Fig 5.1: Layout of HS2 & Midlands Rail Hub

Fig 4.5: HS2 & NPR routes in Northern Powerhouse

Fig 5.2: Connectivity of HS2 & Midlands Rail Hub

Fig 5.3: HSUK Midlands Connectivity

Fig 5.3: HSUK Midlands Ring

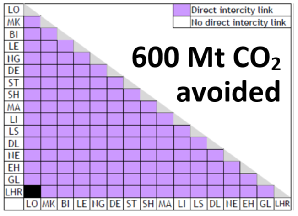

It’s always been difficult to calculate with any precision how many millions of tonnes of CO2 might be saved by the intervention of any particular railway scheme. However, it’s relatively simple to determine which schemes are likely to succeed, and which schemes are likely to fail.

No railway scheme can deliver major CO2 savings in isolation. These savings will only come about if the scheme succeeds in attracting passengers from high-

So a scheme such as HSUK which offers comprehensive direct intercity connectivity (Objective 1), step-

Estimates indicate that HSUK could offer potential CO2 savings of over 600 million tonnes in a 40 year period. By contrast, HS2 Ltd’s own estimates indicate that HS2 will fail to deliver any meaningful reduction in transport sector CO2 emissions

Fig 6.1: HSUK Full Connectivity delivers Step-

Fig 6.2: HS2 Poor Connectivity delivers No Worthwhile Emissions Reductions

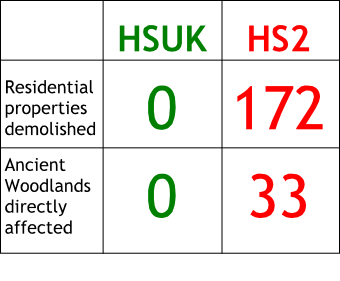

The stark contrast in HSUK’s and HS2’s impact upon communities and the environment is best exemplified by considering the relative effects of HS2’s and HSUK’s routes between London and Birmingham.

There are many possible ways of assessing these impacts but the simplest is to count the number of homes demolished, and the number of Ancient Woodlands directly affected.

HS2’s massive impact on Ancient Woodlands is attributable to its design for the unprecedented speed of 400 km/h, which has dictated the selection of its ultra-

By contrast, HSUK’s chosen route along the M1 corridor will not directly intrude upon any Ancient Woodland, and – with the presence of the M1 having deterred any adjacent residential development – no demolition of residential property should be required.

Table 7.1 : Key Environmental Impacts of HS2 Phase 1 compared with equivalent sections of HSUK

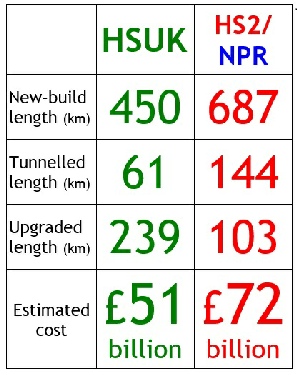

With the HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail proposals concentrated upon interlinking London and the 6 primary cities of the Midlands and the North (i.e. Birmingham, Nottingham, Sheffield, Manchester, Liverpool and Leeds), any meaningful cost comparison must focus upon the works necessary to provide high speed links between these 7 cities.

The cost comparisons undertaken by HSUK are based upon the following:

The works necessary to construct the HS2 ‘Y-

Additional NPR works to interconnect the Northern cities i.e. Sheffield, Manchester, Liverpool and Leeds, and achieve the journey times and service frequencies stipulated in the HS3 Specification (see Objective 4).

Equivalent HSUK new-

HSUK’s cost estimates, all baselined on the £56 billion cost estimated for HS2 in 2015, indicate that HS2 and NPR works will cost around £21 billion (i.e. 40%) more to construct than equivalent HSUK works.

With HS2’s costs now expected to rise to circa £85 billion, this £21 billion difference seems likely to increase to over £30 billion.

These differences can be explained very easily by HSUK’s much more efficient and generally superior routeing strategy, as summarised in Table 8.3.

Put simply, HSUK delivers significantly greater intercity connectivity (see Objectives 1 and 2, and note in particular the inadequacies of the HS2 proposals for East Midlands ‘Interchange’ at Toton, 9km from Nottingham) for significantly shorter lengths of new-

But £21 billion (or more likely £30 billion) is just the start of the financial disaster that is the HS2 project. With the following costs taken into account:

Northward extensions of HS2 to Newcastle, Edinburgh and Glasgow;

Full integration of HS2 with existing network;

the cost differential between the HS2 and HSUK projects could rise to as much as £50 billion.

However, it must be stressed that this is only the difference in construction costs. By the time that the costs arising from:

HS2’s failure to stimulate regional economies (see Objectives 4 and 5);

HS2’s failure to reduce transport CO2 emissions (see Objective 6);

are also taken into account, the true cost differential between HS2 and HSUK could rise to more than £100 billion.

Fig 8.1 : 7 Primary Cities interlinked by HSUK

Fig 8.2 : 7 Primary Cities interlinked by HS2/NPR

Table 8.3 : HS2/NPR vs HSUK Cost Summary

Let’s write that out properly:

£100 billion = £100,000,000,000

All this is public money, and it will be utterly squandered because highly-

“HS2 modelling is shocking, biased and bonkers.”

Margaret Hodge, Chair, Public Accounts Committee

“No economic case for HS2... it will destroy jobs and force businesses to close.”

Institute of Economic Affairs

WATCH OUR VIDEO

HS2’s 2-

HSUK answers the capacity challenge with a 4-

HS2 has been designed in almost complete isolation from the existing rail network; so far, only 5 connections are planned. This is akin to building the M1/M6 between London and Birmingham without any interchanges and only a single lane in each direction.

By contrast, over a comparable area 30 connections are planned to connect HSUK to the existing network.

HS2 proposes to use either new city centre terminus stations (Birmingham, Manchester & Leeds), isolated parkway stations (Birmingham & Nottingham), or existing stations on long spurs (Sheffield).

HSUK will serve through stations, fully integrated with the existing local network, in all major cities.

HS2’s designed new lines extend no further north than Wigan and York, and the selection of a terminus station in Birmingham will effectively sever the CrossCountry network there.

By contrast HSUK has designed over 2,000km of new-

There is no indication that HS2 Ltd has ever developed a timetable either to describe how the national rail network will operate with HS2 in place, or to define the true requirement for new capacity. Indeed, the almost complete lack of integration between HS2 and the existing network makes the development of such a timetable virtually impossible.

HSUK’s development of a timetable has been an essential tool both to demonstrate the practicality of a fully interconnected UK (Objective 1) and the scale of potential journey time reductions (Objective 2), and also to identify the works necessary to achieve the required capacity.

There is no evidence that HS2 Ltd has made any meaningful attempt to design HS2 as an optimised national network.

By contrast, HSUK was designed from the outset with the aim of interconnecting all major UK cities.